ENVIRONMENTAL AWARD

WINNER: John Trotter - No Agua, No Vida: The Human Alteration of the Colorado River

JUROR: Sabine Meyer - National Audubon Society

-

Since 2001, I’ve been photographing the consequences of the sweeping human alteration of the Colorado River, in the Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico. The Colorado, I soon learned, was greatly reduced from what it once was and no longer makes its ancient rendezvous with the Sea of Cortez, between the Baja California peninsula and the Mexican mainland.

Forces north of the border had other destinations planned for the river’s water, and in 1922 divided its annual flow between seven U.S. states and Mexico. They built an extensive network of dams, stilling much of the once- roiling river and creating the foundation on which the Southwestern United States has been built.

But as it has turned out, the foundation of everything, the premise of 1922, was based more on wishful thinking than fact and up to 25% more water has been promised to the river’s users than actually exists.

I’ve taken many trips to the river, documenting its delivery infrastructure, and the cities and farms dependent on it. I am most struck by the profound disconnection that the river’s users have with this vast, glorified plumbing system, which provides them with water - one of the few things in the world without which we cannot survive. Despite years of warnings from scientists, the users have been drawing down the system’s two biggest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, faster than the climate change- depleted river can replenish them. In mid-2022, Lake Powell dropped to its lowest level since becoming operational in the mid-1960s and its continuing decline endangers the entire system below.

As the climate change emergency continues to shrink the Colorado, the only hope for mitigating the inevitable suffering for more than 40 million people directly dependent on the river’s water will be cooperation informed by a better understanding of the system’s totality. Though exploitation of the river has created animosity between its users since even before the 1922 Compact, the stakes have never been higher.

-

As a photo editor working in the non-profit environmental space, I am often asked to define how photography can not only expose but also help environmental issues.

Photography is at its most powerful when it frames - or “reframes” - human impact on our planet, its inhabitants, and its resources in such an effective way that, that very single photo frame, gets us, the viewers, to stand up, say “enough” and take action.

To achieve that goal, the spectrum of photographic tools is wide and varied, with diverse avenues of practice, from documentary photography to fine arts studio creations, to site specific projects, to multimedia and mixed media works.

All of this year’s entries span this expansive definition and made for a very worthy and robust collection of projects that, in turn, question the self, our natural resources, our relationship to our planet and its many living forms and so much more.

No Agua. No Vida: the Human Alteration of the Colorado River rose to the top for me because it lays bare that there is no denying we are experiencing a serious water crisis in the West.

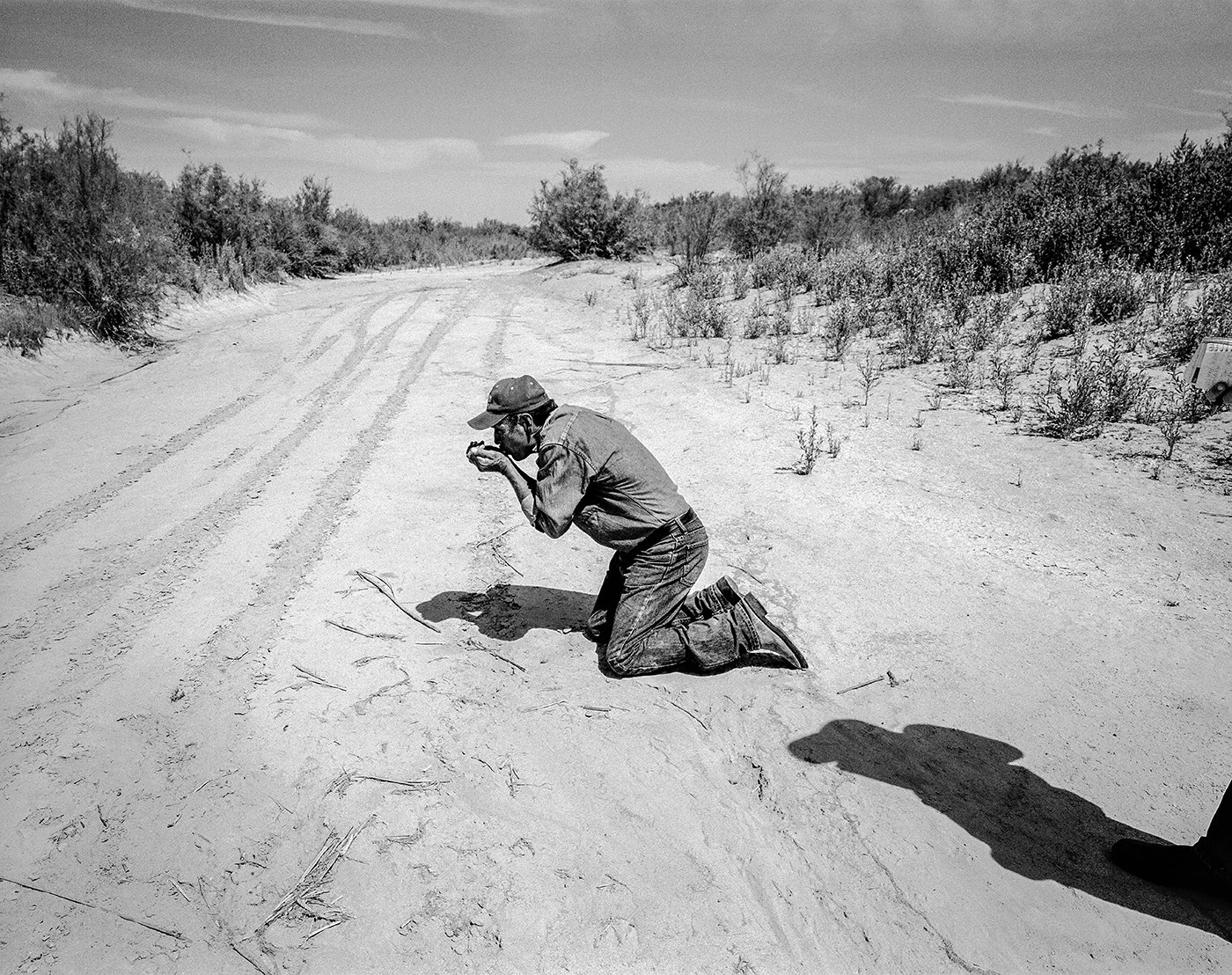

20 years in the making, Trotter’s collection is a series of gorgeous photographs that harken back to the years of the Farm Security Administration's photographic documentation of the Great Depression.

His black-and-white frames are composed with rigor and the minimal but decisive information that encapsulates critical concepts centering around water overuse and hence scarcity, around human alteration of natural water flows and hence downstream consequences on people’s lives and livelihoods, on natural habitats and wildlife.

Trotter is able to balance visual beauty with a stark and harrowing reality - his eye is poetic and unflinching but also compassionate to the people he photographs - he is showing us, not teaching us with his photos.

Let’s hope we learn and take at heart his plea: water is the source of life, and we need to take better care of it.

– Sabine Meyer • Photography Director, National Audubon Society

-

Black and white film + digital images. I propose 16 X 20-inch images with a small number of larger 20 X 24-inch images.

About the Artist

© Robert Clark

John Trotter, 63, worked as a newspaper photojournalist for 14 years, locally and internationally, until March 24, 1997, when he was nearly murdered by a half-dozen young men while on assignment for The Sacramento Bee, where he worked as a staff photographer. After many years in a box, photographs he took during his long recovery from his subsequent brain injury are becoming a book, The Burden of Memory.

In 2001, Trotter began photographing in Mexico for his project No Agua, No Vida about the human alteration of the Colorado River. He has photographed along the entire 2,250 km length of the river, from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the desiccated remains of its delta above the Gulf of California. He has lived in New York City since 2000, and in 2017 became one of the founding members of the collective, MAPS Images.

johntrotterphoto.com